Tomb of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun’s tomb, discovered nearly intact in 1922 by Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings, contained more than 5,000 artifacts preserved for over 3,300 years. Among the treasures were gold chariots, alabaster vessels, jewelry, ornate furniture, and the iconic solid-gold funerary mask. Carter’s team spent ten years documenting all 5,398 objects, transforming modern archaeology and offering unparalleled insight into royal burial practices. The discovery captivated global media and brought worldwide fame to Carter and Lord Carnarvon.

The Discovery That Changed Egyptology

The moment of discovery on November 4, 1922

On November 4, 1922, Howard Carter’s team uncovered the first step of what would become the most important archaeological discovery of the 20th century. For years, Carter had been searching the Valley of the Kings with little success, funded by the English aristocrat Lord Carnarvon. Many believed the valley had nothing left to offer, as most tombs had already been robbed in antiquity.

But that morning changed everything.

A water boy stumbled upon a stone step while clearing debris, revealing the top of a staircase descending into the bedrock. Carter immediately halted all activity to protect the site. Over the next few hours, sixteen steps leading to a sealed doorway emerged. The doorway bore the seal of the necropolis guards—and beneath it, a faint impression of the royal cartouche of Tutankhamun. Carter knew he had found something extraordinary.

He cabled Lord Carnarvon in England with a simple, now-famous message:

“At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley. A magnificent tomb with seals intact.”

Carnarvon and his daughter, Lady Evelyn Herbert, rushed to Egypt, arriving on November 23. When they resumed excavation, the sealed doorway was cleared completely, confirming that the tomb had been breached in ancient times but resealed afterward. Still, the seals were mostly intact—an extremely rare and hopeful sign.

Initial impressions and Carter’s famous words

On November 26, 1922, Carter, Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Arthur Callender gathered to open the sealed doorway that led from the stairway to the first chamber. Carter made a small breach in the plaster, inserted a candle, and peered through the gap as hot air rushed from the sealed room.

For a moment, he said nothing.

When Carnarvon impatiently asked, “Can you see anything?”

Carter whispered his immortal reply:

“Yes… wonderful things.”

As his eyes adjusted, he saw golden beds shaped like animals, painted chests, statues covered with gold leaf, overturned baskets, and the gleam of treasure filling the chamber from floor to ceiling.

Carter later described that moment with reverence, noting that the team stood silently, aware they were in the presence of a long-dead king whose burial had remained untouched through centuries of turmoil.

First look into the antechamber

The antechamber was astonishing—a large room packed with nearly 700 objects arranged in a chaotic but largely undisturbed manner. Unlike other royal tombs, which had been emptied by ancient robbers, Tutankhamun’s antechamber showed only minor signs of intrusion.

Carter recorded an extraordinary variety of objects:

- ebony and ivory statues

- ceremonial chariots dismantled and stacked

- lavish gilded furniture

- alabaster vessels

- chests filled with linens, clothing, and jewelry

- bouquets of dried flowers left by mourners

- and a golden throne featuring an intimate scene of Tutankhamun with his wife, Ankhesenamun

Two sealed doorways hinted at further wonders: one leading to the annex and the other to the burial chamber. The latter still bore the seal of the royal necropolis—evidence it had remained untouched since antiquity.

Clearing the antechamber and documenting its contents would take months; fully recording the entire tomb required ten years.

If you look at the excavation timeline, you’ll learn that it took nearly ten years to record, conserve, and remove the objects. You’ll see that Carter insisted on meticulous photography, cataloging, and restoration, which set new professional standards for archaeology.

Inside the Tomb: A Room-by-Room Exploration

Though modest in size compared to other royal tombs, the content preservation in Tutankhamun’s burial made it unparalleled in archaeological history. Its architecture is surprisingly simple: a short stairway, a sloping corridor, and four chambers.

The antechamber: chariots, beds, and statues

Measuring roughly 7.9 × 3.6 meters, the antechamber was the tomb’s largest room and the first Carter entered. It held:

- four gilded chariots, including hunting and ceremonial types

- three ceremonial beds with animal shapes (lion, cow, hippo)

- two life-size black statues of Tutankhamun guarding the sealed doorway

- a golden shrine-like chest

- weapons, shields, bows, and quivers

- daily-use items such as sandals, clothing, and containers

- the golden throne, one of the most celebrated pieces in the entire tomb

The throne alone revealed much about the young king’s life: its delicate scene of Ankhesenamun anointing the king reflects the intimate artistic style of the Amarna period.

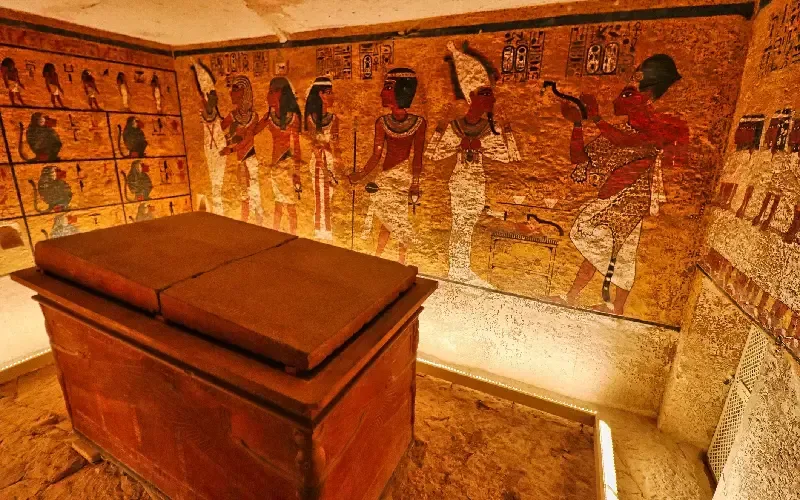

The burial chamber: nested coffins and golden mask

The burial chamber, though small, was the spiritual heart of the tomb. Its walls were painted with scenes of the king’s funeral and his acceptance into the company of the gods. Four golden shrines filled almost the entire space, leaving little room to maneuver.

Inside these shrines rested:

1. A stone sarcophagus with four protective goddesses carved on each corner

2. Three nested coffins:

- the outer two made of gilded wood

- the innermost made entirely of solid gold, weighing about 110 kg

3. The mummy of Tutankhamun, wrapped in linen and adorned with amulets

4. The iconic golden mask, weighing 10.23 kg and inlaid with lapis lazuli, quartz, and obsidian

The burial chamber contained four niches, each holding a “magic brick” inscribed with protective spells from the Book of the Dead to guard the king’s journey into the afterlife.

The treasury: canopic shrine and Anubis statue

Behind the burial chamber lay the treasury, the most sacred room after the burial itself. Roughly 4 × 3.6 meters, this room held objects related to ritual protection and funerary rites.

Its centerpiece was:

- the gilded canopic shrine, adorned with protective goddesses

- an alabaster chest containing the king’s mummified organs

- the statue of Anubis in jackal form, crouched atop a shrine

- boats, models, and ritual equipment meant to accompany the king

Carter described the treasury as feeling “alive with presence,” as though the objects still performed their ancient protective roles.

The annex: everyday items and offerings

The annex, though the smallest room, contained nearly half of the tomb’s total contents—more than 2,000 pieces. It held:

- food offerings such as meats, breads, figs, and wine

- games and recreational items

- oils, perfumes, cosmetics

- baskets, tools, jars, and clothing

- ritual objects of uncertain purpose

The annex was extremely cluttered, with objects piled atop one another. Archaeologists had to be suspended from ropes to reach all items safely.

If you visit the tomb, you’ll see that it has four main chambers: the antechamber, the burial chamber, the treasury, and the annex. Each chamber was designed to hold specific items for the king’s afterlife.

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

Plan Your Trip

Hidden Secrets Archaeologists Never Expected

Tutankhamun’s meteorite dagger

One of the most remarkable objects recovered was an iron dagger with a gold handle. Scientific testing confirmed the blade was made from meteoritic iron—a material more precious than gold in Bronze Age Egypt. Its extraterrestrial origin symbolized divine power, linking the king with the heavens.

Two mummified fetuses in the treasury

In the treasury’s northeastern corner lay two tiny coffins containing stillborn daughters of Tutankhamun and likely Ankhesenamun. Carefully mummified and wrapped with royal care, one fetus even wore a small gilded mask. CT scans later revealed they suffered no congenital deformities, correcting earlier assumptions.

Unusual resin damage to the mummy

During mummification, priests coated the king’s body with a heavy amount of hot resin, which hardened like glue. Carter’s team could not separate the mummy from the golden coffin and ultimately dismembered the body to remove it. The mummy was reassembled later, though the damage remained irreversible.

The tomb’s small size and rushed construction

Tutankhamun’s tomb is unusually small for a pharaoh. Evidence suggests his death at around age 19 was unexpected, leaving little time to prepare a grand burial. Painters completed only three of the four walls with the same finishing layer; the fourth wall appears rushed.

Reused artifacts from earlier reigns

Many objects—including shrines, coffins, and even the sarcophagus—show signs of having been repurposed from earlier burials. Names were chiseled out and replaced with Tutankhamun’s. This suggests the burial was assembled quickly, drawing on prepared objects from other tombs or workshops.

Black cumin seeds and their symbolic meaning

Black cumin seeds, found throughout the tomb, were valued for spiritual and medicinal properties. Associated with healing and protection, they were believed to support the king’s health in the afterlife.

One of the surprises you’d learn about is the presence of two mummified fetuses, thought to be Tutankhamun’s stillborn daughters. You’d also hear about a dagger made from meteorite iron and clear evidence that the tomb was prepared quickly, such as unfinished paintings.

The Aftermath: Controversy, Curse, and Control

The media frenzy and rise of ‘Tutmania’

The discovery unfolded just as modern mass media was gaining power. Carnarvon sold exclusive reporting rights to The Times, angering other journalists. Soon, newspapers everywhere were filled with images and stories of the treasure-filled tomb.

This sparked a global cultural phenomenon:

- Art Deco designs incorporated Egyptian motifs

- Fashion began using Egyptian patterns and colors

- Songs, posters, films, and plays referenced Tutankhamun

- Jewelry and cosmetics were inspired by the golden mask

The young king, forgotten for millennia, became the symbol of ancient Egypt.

The curse of the pharaohs

When Lord Carnarvon died unexpectedly in April 1923 from an infected mosquito bite, sensationalist newspapers claimed it was the result of a “pharaoh’s curse.” Rumors spread quickly:

- lights went out in Cairo the moment Carnarvon died

- his dog in England supposedly howled and died simultaneously

- other members of the expedition died in later years, fueling speculation

Howard Carter dismissed all of this as nonsense, but the idea of a supernatural curse became a permanent part of popular culture.

Disputes over artifact ownership and access

The discovery intensified debates over cultural heritage and colonial control. Egyptians criticized the exclusion of local journalists and the Western monopoly on excavation rights. Today, Egypt continues to advocate for the repatriation of artifacts believed to have been removed unlawfully. The 2020 controversy over a Tutankhamun bust sold at Christie’s reignited the debate, with Egypt asserting the piece was stolen from Karnak.

When you look into the famous “curse,” you’ll find that it originated from media sensationalism rather than ancient writings. You’ll notice that no curse was inscribed in the tomb, and most people involved in the excavation lived long, normal lives. Scientists today explain reported deaths as coincidences or natural causes, not supernatural events.

The discovery sparked a global fascination with ancient Egypt, shaping fashion, art, literature, and media throughout the 20th century. It also fueled the widespread popularity of the “pharaoh’s curse” legend, even though no actual curse was found in the tomb.

More than 5,000 objects were uncovered, including gilded chariots, jewelry, statues, canopic jars, and an enormous collection of funerary items. The meteorite-iron dagger and the iconic gold mask are among the most remarkable pieces.

It is the most complete royal burial ever discovered in Egypt, preserved almost exactly as it was left in antiquity. This offers an unmatched view of 18th-Dynasty craftsmanship, daily life, and religious practices.

Its small size and hidden location helped protect it. Only minor robberies occurred in antiquity, and debris from nearby tomb construction later buried the entrance, keeping it concealed for more than 3,000 years.

The paintings illustrate rituals connected to the king’s rebirth, including the “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony. They also show gods such as Osiris and Anubis guiding Tutankhamun into the afterlife.

The inner coffin is made of solid gold and weighs over 100 kg. Its intricate details and inlays of lapis lazuli and quartz highlight the exceptional artistry of the 18th Dynasty, making it a masterpiece of ancient craftsmanship.

CT scans, DNA testing, and 3D mapping have shed light on the king’s health, family lineage, and burial practices. Digital imaging has also revealed hidden details in the tomb’s artwork and helps monitor preservation conditions.