Medinet Habu

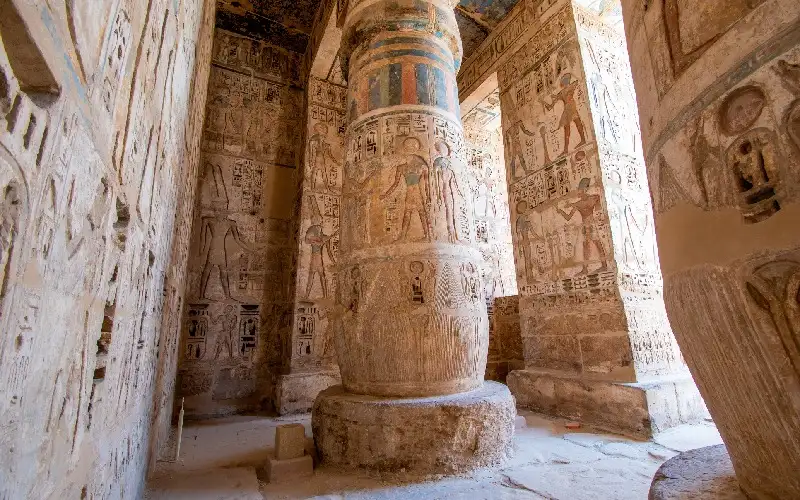

Egypt's archaeological landscape holds few sites as captivating as Medinet Habu, where the sands of the 12th century BCE conceal one of the nation's most remarkable temple complexes. This monument rises near the Theban Hills, strategically along the Nile's West Bank. The sprawling precinct, measuring 210 meters by 300 meters, shelters more than 7,000 square meters of decorated wall reliefs, each whispering tales from pharaonic Egypt's golden age.

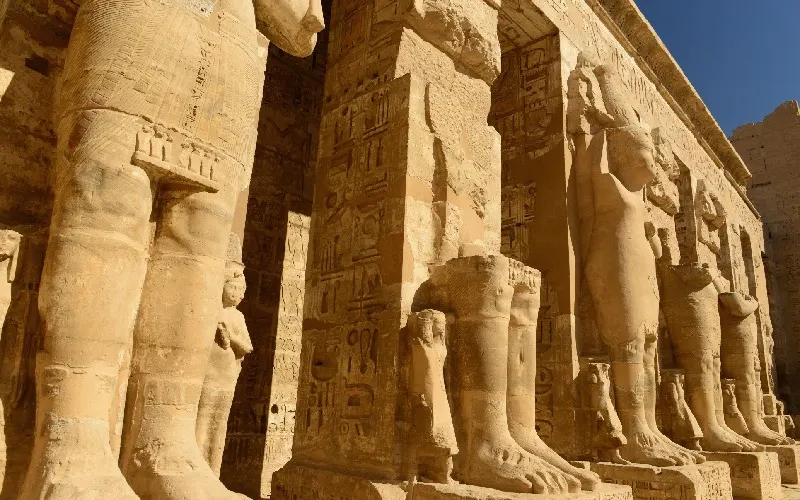

Ramesses III's mortuary temple forms the heart of this wonder, its walls bearing inscriptions of the pharaoh's defining military encounters. These stones record the Sea Peoples, maritime warriors who challenged Egypt during his reign between 1186 and 1155 BCE. The Battle of the Delta unfolds across these walls, captured in stone. Massive fortification walls encircled the complex, interrupted only by an eastern pavilion gate for royal processions. Religious scenes and battle victories coexist on the exterior walls, showcasing Ramesses III's military prowess and divine kingship.

Medinet Habu is one of Egypt's most important archeological sites, featuring the well-preserved mortuary temple of Ramesses III. It contains over 7,000 square meters of decorated wall reliefs, including crucial historical inscriptions about the pharaoh's military campaigns and the defeat of the Sea Peoples.

Origins and Early History of Medinet Habu

Millennia before Ramesses III claimed this ground, the earth beneath Medinet Habu was considered sacred. This terrain held the resting place of the Ogdoad—eight primordial deities predating creation. Tradition held this spot as the primeval mound, the first land to emerge when primordial waters receded.

The significance of the site before Ramesses III

During the 11th dynasty (2081–1938 BCE), builders erected a modest shrine, establishing a spiritual legacy. Known as Djanet, this site marked where Amun first manifested, attracting Theban devotees.

The role of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III

Hatshepsut and Thutmose III expanded the shrine into the "Small Temple," honoring Amun and the Ogdoad. After Hatshepsut's death, Thutmose III completed the sanctuary, removing traces of her influence.

Etymology and ancient names of Medinet Habu

Egyptians called it "Djamet," meaning "males and mothers." Centuries later, Coptic Christians named it "Jeme." European travelers recorded variations like "Habu" and "Medinet Tabu." Under Thutmose III, it became Western Thebes’ administrative center, a role Ramesses III expanded.

The inscriptions at Medinet Habu are invaluable for understanding ancient Egyptian military history. They provide detailed accounts of Ramesses III's campaigns, particularly against the Sea Peoples, offering unique insights into Mediterranean migrations and warfare during the New Kingdom period.

The Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III

Ramesses III's mortuary temple is Medinet Habu's crown jewel, exceptionally preserved, and the last monumental funerary structure of the New Kingdom in Western Thebes.

Architectural layout and dimensions

The temple spans 210 by 300 meters, with decorated reliefs over 7,000 square meters. The building extends 150 meters, containing 48 chambers, including eight mortuary rooms. Visitors pass through the first pylon into a courtyard with colossal Osirid statues, then through the second pylon into a peristyle hall and the second court, reaching the hypostyle hall, now roofless.

Purpose and religious function

Known formally as "The Temple of Usermare-Meriamon," the structure honored Amun while facilitating the pharaoh's eternal journey. Sacred areas housed shrines for Ramesses III, a solar chapel, and an Osiris complex, connecting him to Re and Osiris. The central shrine honored Amun, flanked by Mut and Khons.

Comparison with the Ramesseum

Medinet Habu mirrors the Ramesseum, with slight modifications like single colonnades instead of double. Its exceptional preservation allows visitors to experience its grandeur vividly.

Medinet Habu is notable for its massive fortified enclosure wall and distinctive eastern entrance known as the pavilion gate. The complex includes a large mortuary temple, smaller temples, and chapels. Its well-preserved state allows visitors to see original paintings and architectural details that have been lost in many other ancient Egyptian sites.

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

Plan Your TripMilitary Inscriptions and Historical Records

The walls chronicle detailed campaigns, highlighting Ramesses III as a divine warrior. Depictions of the Sea Peoples include distinctive ships, feathered helmets, and accompanying women and children, suggesting migrations rather than simple raids.

Depictions of the Sea Peoples and Libyan campaigns

Thirteen battle scenes on the northern wall show campaigns against Libyan forces and the Sea Peoples. Egyptian archers and infantry engage in combat while enemy populations are depicted in carts.

Battle inscriptions from Year 5, 8, 11, and 12

Year 5 records the First Libyan War; Year 8, the Northern War; Year 11, the Second Libyan War; and Year 12 summarizes victories.

Symbolism in military reliefs

The reliefs present Ramesses III actively leading battles, reinforcing his divine authority. Enemy ships and shields differ from Egyptian designs.

Topographical lists and king list

The south tower lists 125 Levantine locations; the north tower, Nubian sites. The king list shows Ramesses III at the Festival of Min with his royal predecessors.

Originally a sacred site associated with the Ogdoad and Amun, Medinet Habu transformed into Ramesses III's mortuary temple, then an administrative center, and later a Coptic settlement called Djeme. This evolution reflects broader patterns of Egyptian religious, political, and social development across millennia.

Later Additions and Cultural Layers

Medinet Habu reveals layers of cultural evolution over nearly two millennia, including contributions from the 20th, 25th, 26th, 29th, and 30th dynasties, and the Greco-Roman period.

The Small Temple and its restoration

The Small Temple, dedicated to the Ogdoad and Amun, was restored between 1996–2006 with USAID support. Conservators sealed roofs, cleaned reliefs, and reconstructed sandstone flooring.

Saite chapels and Divine Adoratrices

Funeral chapels honor Divine Adoratrices—royal women of the 25th and 26th dynasties. Figures like Amenirdis, Shepenwepet, and Nitocris exercised extraordinary authority, reflected in these well-preserved chapels.

Coptic settlement and transformation into Djeme

Between the 1st–9th centuries AD, Medinet Habu became the Coptic city of Jeme, housing roughly 18,860 residents. A five-aisled basilica was built within the temple, blending Christian and pharaonic architecture.

Archaeological excavations and modern discoveries

Excavation began 1859–1899 under Auguste Mariette. Later, the Oriental Institute of Chicago documented reliefs and statues, including the Thutmose III and Amun dyad. Some Greco-Roman and Byzantine structures were lost.

Medinet Habu illuminates centuries of Egyptian civilization. Military inscriptions detail Ramesses III's campaigns against the Sea Peoples, while preserved architecture reveals religious rituals, administrative practices, and artistic achievements. Sacred spaces, mortuary ceremonies, and Coptic adaptations show the temple’s evolving role. Archaeological work continues, promising more discoveries beneath the desert sands.

The correct pronunciation of Medinet Habu is "meh-din-ET HA-boo".

The Sea Peoples were a confederation of maritime groups who threatened Egypt during Ramesses III's reign. Medinet Habu contains the most detailed visual and textual records of their battles, providing crucial evidence of their military strategies and interactions with ancient Egypt.

The Small Temple, located near the entrance, was dedicated to the Ogdoad and Amun. It predates Ramesses III’s mortuary temple and was expanded by Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Today, it has been partially restored to preserve its historical and religious significance.

The Divine Adoratrices were royal women who governed Upper Egypt on behalf of the pharaoh during the 25th and 26th dynasties. Their chapels at Medinet Habu highlight their political and religious influence, a rare example of female authority in ancient Egypt.

Between the 1st and 9th centuries AD, the site became the Coptic city of Djeme, with residents constructing churches and living within the temple walls. The Holy Church of Djeme, built inside the second courtyard, represents a fusion of Christian and ancient Egyptian architecture.

Excavations began in the 19th century under Auguste Mariette, and the Oriental Institute of Chicago has conducted systematic documentation since 1924. Restoration efforts have stabilized structures, cleaned reliefs, and reconstructed floors, allowing scholars and tourists to study the site while preserving its integrity.