Valley of the Queens in Luxor

Ta-Set-Neferu—this ancient Egyptian name whispers secrets from millennia past, carrying within its syllables the dual essence of "The Place of Beauty" and "The Place of the Royal Children." Nestled at the southern end of the Theban hillside, this remarkable archaeological treasure unfolds across a landscape where 91 tombs rest within the main wadi, while several subsidiary valleys cradle an additional 19 burial chambers.

More than 90 known tombs lie scattered across the Valley of the Queens near Luxor, yet only a select few welcome visitors today. Recognition of its extraordinary significance came in 1979 when UNESCO inscribed the Valley of the Queens onto its World Heritage List, joining the illustrious company of the Valley of the Kings, Karnak, Luxor, and other precious Theban sites. Among these ancient sepulchers, one tomb reigns supreme—that of Nefertari, beloved queen of Ramses II, hailed as the most exquisite jewel of the Theban necropolis.

The first systematic exploration of this sacred ground unfolded between 1901 and 1903 under Italian archaeologists Ernesto Schiaparelli and Francesco Ballerini, whose work continues to unlock the mysteries of ancient Egyptian royal burial traditions.

There are over 90 known tombs in the Valley of the Queens. The main wadi contains 91 tombs, while several subsidiary valleys add another 19, totaling more than 110 tombs. However, only a few are currently open for tourist visits due to conservation efforts.

The Origins and Purpose of the Valley of the Queens

West of the Nile near Luxor, this necropolis emerged as a remarkable testament to evolving royal burial practices, ultimately sheltering over 90 known tombs spanning the New Kingdom period (1550–1070 BCE). Initially a modest burial ground for royal children and courtiers during the 18th Dynasty, it gradually transformed into the exclusive final resting place for queens, particularly during the influential Ramesside period.

Why it was chosen as a burial site

The selection of this valley reflected a combination of practical necessity and sacred tradition. Security concerns prompted pharaonic architects under Thutmose I (1506–1493 BCE) to shift royal burials west of the Nile, where rugged terrain offered protection against tomb robbers.

Additional factors influenced the choice:

- A sacred grotto dedicated to Hathor stood at the valley's entrance, believed to aid in the deceased’s rejuvenation.

- The nearby artisan village of Deir el-Medina allowed skilled workers easy access.

- Geological formations offered both natural protection and privacy.

- Alignment with established ritual pathways supported Theban festival traditions.

- Geographically, it balanced the necropolis: kings in the Valley of the Kings, queens in the southern valley.

The meaning of Ta-Set-Neferu

The ancient name “Ta-Set-Neferu” carries dual significance. Commonly interpreted as "The Place of Beauty," it references the valley’s physical splendor and spiritual purpose. An alternative translation, "The Place of the Royal Children," reflects its original function as a burial ground for princes and princesses, mirroring the valley’s evolution from children’s tombs to the resting place of queens.

Relation to the Valley of the Kings and Deir el-Medina

The Valley of the Queens functioned within a carefully planned mortuary complex, alongside the Valley of the Kings and Deir el-Medina. Situated 1.5 miles west of Ramses III's mortuary temple at Madīnat Habu, the location facilitated tomb construction and decoration. Skilled artisans from Deir el-Medina accessed the valley via the Valley of the Dolmen, ensuring exceptional artistry for each royal tomb. While queens’ tombs were smaller than pharaohs’, they featured equally exquisite decoration, highlighting the elevated status of royal women during the New Kingdom.

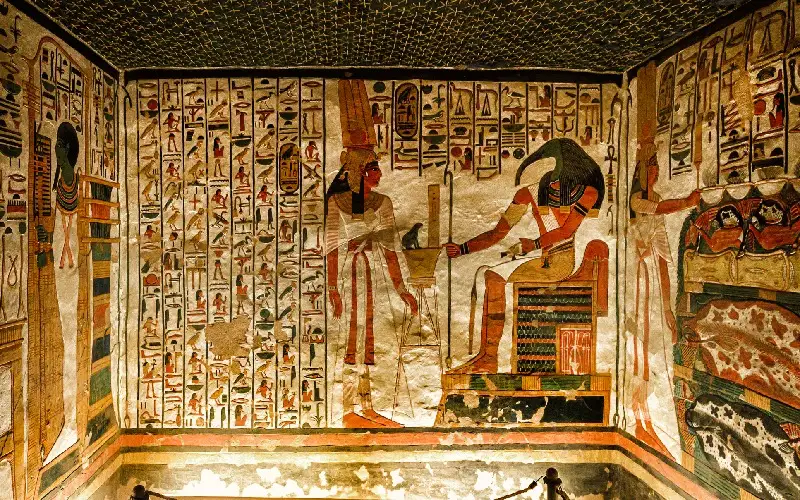

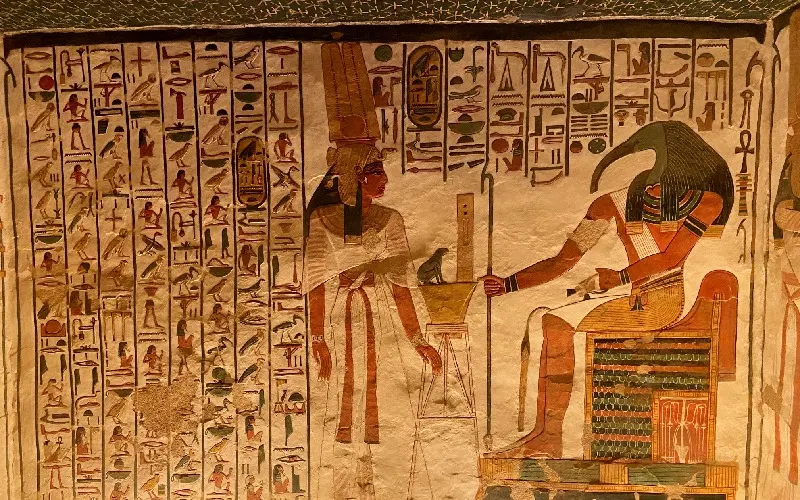

The Valley of the Queens is home to numerous tombs, with Queen Nefertari's tomb (QV66) being the most spectacular. Other notable tombs include those of Prince Amun-her-khepeshef (QV55), Queen Tyti (QV52), and various other royal family members. These tombs feature intricate wall paintings and provide insights into ancient Egyptian burial practices.

Tombs of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties

Eighteenth Dynasty: Simpler tombs and early burials

Princess Ahmose, daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Queen Sitdjehuti, holds the distinction of the valley’s earliest recorded burial. During the 18th Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE), the necropolis primarily served royal children and high-ranking officials rather than queens. Fifty-seven tombs from this era lie within the main valley, with twenty more in subsidiary valleys. Vertical shafts led to one or more burial chambers, gradually expanded over generations. Tombs QV17, QV69, QV78, and QV82 exemplify this adaptive reuse.

Nineteenth Dynasty: Rise of royal women's tombs

The 19th Dynasty (circa 1292 BCE) transformed the valley into an exclusive burial ground for royal women. Queen Sat-Re’s tomb (QV38), likely begun under Ramesses I and completed by Seti I, marks this transition. Tombs became more complex, with multi-chambered layouts, entrance ramps, and sumptuous decoration. Queen Nefertari's tomb (QV66) represents the pinnacle of this artistic and architectural development, often described as the “Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt.”

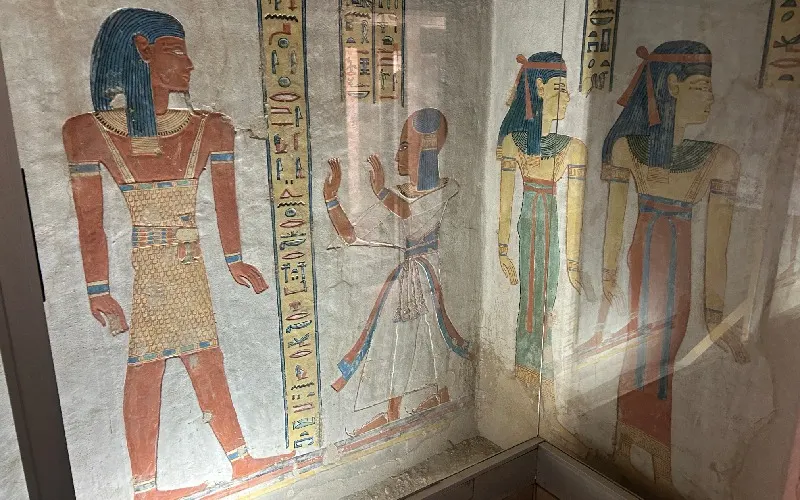

Twentieth Dynasty: Inclusion of royal sons and economic decline

The 20th Dynasty (1189–1077 BCE) expanded burial privileges to include royal sons. Tombs of Ramesses III’s children—Amun-her-khepeshef (QV55), Khaemwaset (QV44), Pareherwenemef (QV42), Ramesses Meryamun (QV53), and Seth-her-khopeshef (QV43)—stand as remarkable monuments. This period, however, also reflects economic decline. Labor unrest, exemplified by a workers’ strike in Year 29 of Ramesses III, and escalating tomb robberies reveal broader societal instability leading to the New Kingdom’s eventual collapse.

The Valley of the Queens served as a burial ground for royal wives, particularly those of Ramesses I, Seti I, and Ramesses II. It also contains tombs of princes and other royal children. The most famous burial is that of Queen Nefertari, whose tomb is renowned for its well-preserved polychrome reliefs.

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

Plan Your TripNotable Tombs and Individuals Buried

Queen Nefertari and her iconic tomb

Ernesto Schiaparelli’s 1904 discovery of QV66 unveiled Nefertari’s tomb, famed for its 5,200 square feet of vivid wall paintings depicting the queen’s journey through the afterlife. Despite past looting and environmental damage, meticulous restoration between 1986 and 1992 preserved its masterpieces, from delicate facial features to ornate ceremonial scenes.

Tombs of princes like Amunherkhepshef and Khaemwaset

Prince Amunherkhepshef (QV55) served as royal scribe and cavalry commander before dying at age 15. QV44 holds Prince Khaemwaset’s burial, notable for painted reliefs and over forty wooden sarcophagi from later reuse during the 25th–26th Dynasties, reflecting the tomb’s communal adaptation.

Other queens and royal children

Queen Tyti, wife of Ramesses III, rests in QV52; Merytamen, daughter and Great Wife of Ramesses II, in QV68; Queen Iset Ta-Hemdjert (QV51) and Prince Ramesses Meryamen (QV53) also add to the valley’s rich roster. Each tomb offers unique insights into New Kingdom funerary practices and the elevated status of royal women.

The Valley of the Queens, known anciently as Ta-Set-Neferu, is a crucial archeological site that provides insights into ancient Egyptian burial practices and the evolving status of royal women during the New Kingdom period. It was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979 along with other Theban sites.

Archaeological Discoveries and Conservation Challenges

Early excavations by Schiaparelli and Ballerini

Italian archaeologists Schiaparelli and Ballerini conducted the first systematic excavations (1903–1906), uncovering Nefertari’s tomb (QV66) in 1904 and Prince Khaemwaset’s tomb (QV44) in 1903. Schiaparelli’s mudbrick kitchen building remains at the site as a testament to these pioneering efforts.

Geological threats: clay shrinkage, salt damage

The valley’s limestone, marl, clay, chalk, and shale foundation is prone to flash floods. Clay expansion and shrinkage, combined with salt crystallization from groundwater, have damaged tomb walls and artworks, necessitating ongoing conservation.

Impact of tourism and bat colonies on preservation

Before visitor restrictions, high tourist volumes elevated carbon dioxide levels beyond safe thresholds, accelerating deterioration. Bats residing in tombs caused further damage through urine and guano, while posing health risks like histoplasmosis. Controlled visitation and active preservation now help mitigate these threats.

Ta-Set-Neferu emerges as more than a collection of tombs—it is a window into New Kingdom Egypt, where sacred, political, and artistic endeavors converged. The necropolis evolved from a burial ground for royal children into a sanctuary for queens, reflecting social transformation over centuries.

Schiaparelli and Ballerini’s pioneering excavations revealed both the artistry and vulnerabilities of this ancient site, highlighting technical mastery and ongoing preservation challenges. UNESCO’s 1979 designation affirmed its place within the Theban mortuary complex, alongside the Valley of the Kings and Deir el-Medina.

The Valley of the Queens documents the elevated status of royal women, the evolution of funerary practices, and the enduring human quest to confront mortality through beauty and ritual. Its tombs continue to inspire awe, providing profound insights into one of history’s most remarkable civilizations over three millennia later.

The Valley of the Queens faces several preservation challenges, including geological threats from unstable rock formations, flash floods, and salt crystallization. Additionally, past unrestricted tourism and the presence of bat colonies have contributed to the deterioration of wall paintings in many tombs. Ongoing conservation efforts aim to protect these invaluable historical treasures.

The best time to visit is during the cooler months from October to April, when temperatures are more comfortable for exploring the tombs and surrounding desert landscape.

Yes, guided tours are available and highly recommended. Knowledgeable guides provide historical context, explain tomb artwork, and share stories about the royal individuals buried there.

Photography is generally prohibited inside most tombs, including Queen Nefertari’s, to protect the delicate wall paintings from light damage. Visitors may take photos in outdoor areas of the valley.

The valley is located on the west bank of the Nile near Luxor. Visitors can reach it by car, taxi, or organized tour from Luxor city, usually combined with visits to the Valley of the Kings and nearby mortuary temples.

Access can be challenging due to uneven terrain, stone steps, and narrow tomb passages. Some areas may not be suitable for wheelchairs or those with limited mobility, so it’s recommended to plan accordingly.