Deir El-Medina

Deir el-Medina stands as one of ancient Egypt's most remarkable archaeological sites, an entire workmen's village dating back over 3,000 years. Established at the start of the 18th Dynasty in western Thebes (modern-day Luxor), this settlement thrived throughout the New Kingdom period (1550–1080 BCE) and served a singular purpose. Known to its inhabitants as "Set Maat" or "Place of Truth," the village housed the highly skilled artisans responsible for constructing and decorating the magnificent tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

At its peak, this community contained approximately sixty-eight houses spread across 5,600 square meters. Despite its relatively modest size, Deir el-Medina flourished for nearly 500 years and was home to an elite workforce whose craftsmanship adorned the final resting places of Egypt's most powerful pharaohs. The inhabitants were officially designated as "Servants in the Place of Truth," reflecting their prestigious role in creating these sacred spaces.

Furthermore, the archaeological significance of Deir el-Medina extends beyond its physical structures. More than 5,000 ostraca (limestone flakes with writing) have been uncovered at the site, providing unprecedented insights into daily life during this period. These texts reveal fascinating details about tomb robberies, divorce proceedings, women's property rights, economic conditions, worker strikes, and even medical treatments for ailments like scorpion bites and blindness. Consequently, the village was eventually abandoned around 1110–1080 BCE during Ramesses XI's reign due to increasing threats from tomb robbery, Libyan raids, and civil unrest.

The Origins and Purpose of Deir el-Medina

The ancient Egyptian settlement now known as Deir el-Medina originated as a carefully planned community with a singular purpose—to house the skilled craftsmen responsible for creating royal tombs.

Founded under Thutmose I during the 18th Dynasty

The earliest archaeological evidence at Deir el-Medina dates to the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose I (c. 1506–1493 BCE), although some inscriptions credit his predecessor Amenhotep I with planning the settlement. Initially, the village was modest, containing approximately forty houses surrounded by a protective wall. The community expanded continuously thereafter, reaching its zenith during the reigns of Seti I and Ramses II, when it grew to include fifty houses inside the walls and seventy additional dwellings outside.

Known to its inhabitants by several names, the settlement was called:

- "Set Maat" (The Place of Truth) in ancient Egyptian

- "Pa Demi" (The Village) in common reference

The craftsmen themselves were known as "Servants in the Place of Truth," reflecting their sacred duty to create eternal resting places for divine kings.

Strategic location near the Valley of the Kings

The site's position was carefully selected for both practical and security purposes. Nestled in a small natural amphitheater in the Theban hills, Deir el-Medina sat within easy walking distance of the Valley of the Kings. Its proximity to the Valley of the Queens and various funerary temples made it an ideal base for workers servicing multiple royal necropolises.

Why secrecy and isolation were essential

The primary reason for establishing this isolated community was to preserve the secrecy surrounding royal tomb construction. By housing workers separately, authorities could control information about tomb locations, designs, and security measures. The state supplied all necessities, including water from the Nile, ensuring dependence on royal authority while limiting outside contact. Guard houses at the north and south walls reinforced security and restricted access.

Deir el-Medina was a village built to house the skilled artisans responsible for constructing and decorating the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings during ancient Egypt's New Kingdom period.

The village of Deir el-Medina was inhabited for nearly 500 years, from the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (around 1550 BCE) until its abandonment around 1110-1080 BCE during the reign of Ramesses XI.

Inside the Village: Architecture and Daily Life

The tightly packed mud-brick homes of Deir el-Medina reveal fascinating insights into the daily routines and domestic arrangements of Egypt's royal tomb builders.

Layout of homes and streets

The village featured a rectangular layout enclosed by a protective wall, containing approximately 68 houses over 5,600 m². A single street ran the length of the settlement, possibly covered to shelter villagers from the sun. Each home averaged 70 m², typically consisting of:

- A receiving room entering from the street

- A main living area with a mudbrick platform

- One or two smaller rooms for sleeping and storage

- An open-air kitchen with stair access to the flat roof

Houses featured whitewashed walls, high windows, small altars, and niches for statues.

Work schedules and rest days

Workers followed an eight-day work cycle with two days off. Absences occurred due to illness, family matters, or personal reasons. During major festivals, over a third of the year could be time off. Male artisans stayed near the Valley of the Kings in temporary housing during tomb construction shifts, typically lasting 8–10 days.

Food, water supply, and household roles

Water was transported from the Nile daily. Food arrived as rations, primarily grain, while women baked bread, brewed beer, and stored perishables in underground pits. Extensive bartering existed for goods such as sandals, beds, and toys.

Education and literacy among villagers

Many inhabitants, including women, could read and write. Boys learned from fathers, girls from mothers. Literacy allowed extensive documentation of village life on ostraca and papyri.

The thousands of ostraca and papyri discovered at Deir el-Medina provide unprecedented insights into daily life in ancient Egypt, including information about legal proceedings, work schedules, religious practices, and even the world's first recorded labor strike.

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

Plan Your TripSocial Order, Law, and Justice

The village maintained a structured hierarchy to manage work and community life.

Roles of foremen, scribes, and laborers

The workforce divided into the "Right Gang" and "Left Gang," each led by a foreman appointed by the Vizier. Scribes recorded work, tracked absences, and managed tools. Deputies distributed supplies in the foreman’s absence. Specialized roles included draftsmen and chisel bearers, while guardians protected tools and materials.

Inheritance and job succession

Positions were often hereditary, passing from father to son. Foremen chose deputies from their own families, occasionally causing tension. Property inheritance followed strict rules, prioritizing burial caretakers.

Village court system and famous legal cases

The kenbet court handled civil and minor criminal disputes. Notable cases include Menna suing the chief of police over unpaid goods and Herya accused of stealing temple property. These legal proceedings reveal community self-governance and adherence to justice.

Strikes and labor unrest under Ramesses III

In the 29th year of Ramesses III’s reign, workers staged one of history’s first recorded strikes over insufficient grain rations. Scribe Amennakhte petitioned the authorities, stating, "we are dying, we cannot live." The strike prompted payment, but unrest continued intermittently.

The village had a complex hierarchy, with foremen at the top, followed by scribes, deputies, and workers. Positions were often inherited, passing from father to son, and the community had its own court system to handle disputes.

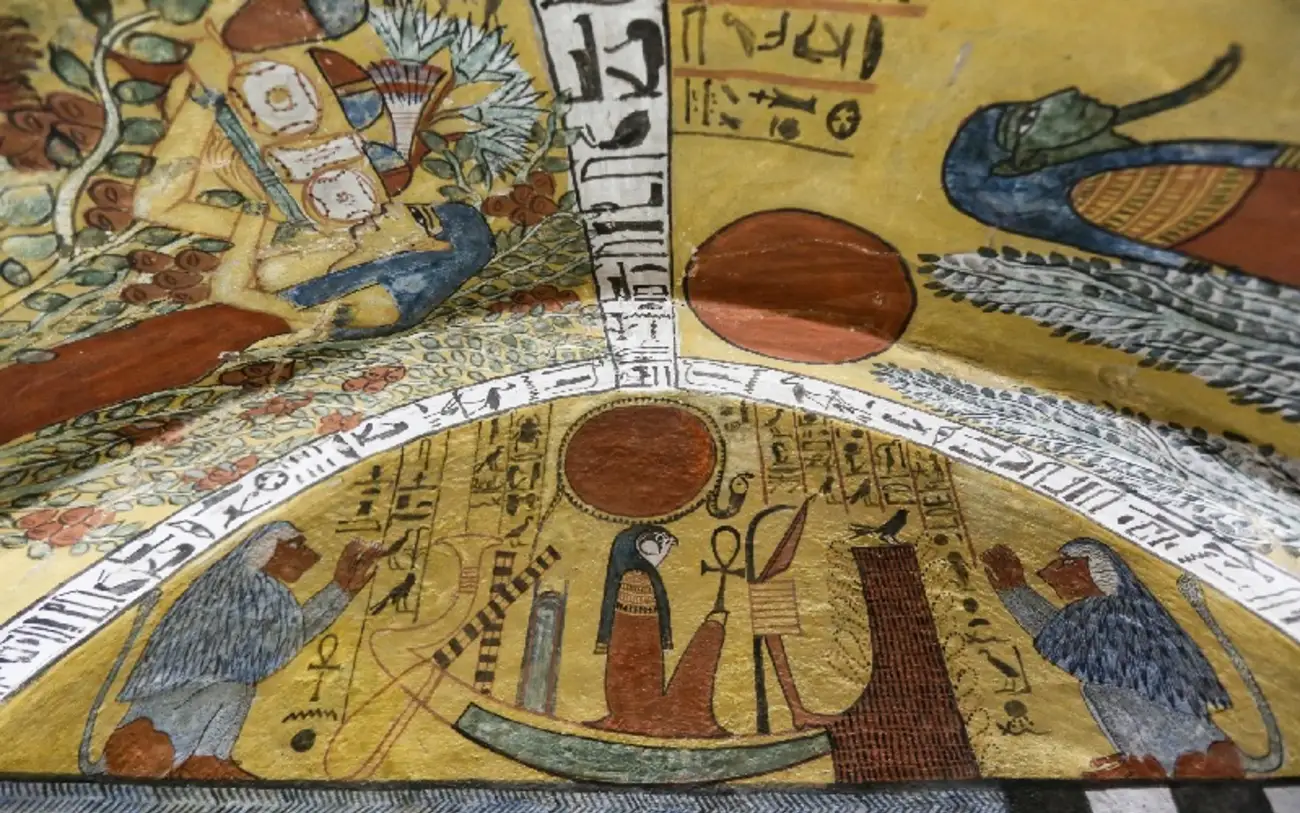

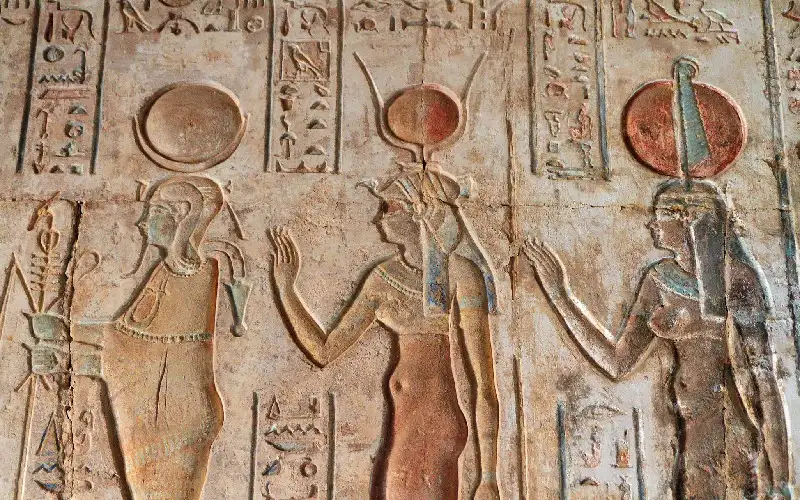

Religion, Rituals, and Personal Beliefs

Religious practice permeated life, with specialized local traditions.

Worship of Hathor, Ptah, and Meretseger

Meretseger, the cobra goddess, protected the Theban necropolis and punished lawbreakers. Hathor was revered as a domestic goddess and Ptah as patron of craftsmen. Confession stelae reveal villagers seeking forgiveness for transgressions.

Deified figures: Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nefertari

Amenhotep I and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari were worshiped locally for over 400 years. Annual festivals celebrated these figures, with elders performing ceremonial duties. Amenhotep I also functioned as an oracle, guiding villagers through interpreted movements of his statue.

Use of oracles and dream interpretation

Dreams were integral to religious life. Records from Scribe Kenhirkhopeshef’s library demonstrate interpretations that often contradicted literal dream content. Oracles supplemented divine guidance.

Private chapels and household altars

Almost all homes contained altars and niches. Thirty non-funerary chapels in the northern village area served collective worship and gatherings. False doors allowed ancestor interaction and spiritual communication.

Residents of Deir el-Medina worshiped various deities, including Meretseger, Hathor, and Ptah. They also uniquely venerated the deified royal figures Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nefertari. Most homes contained private altars, and the community used oracles and dream interpretation in their religious practices.

Deir el-Medina offers unparalleled insight into ancient Egyptian daily life. Unlike sites highlighting only elite tombs, this village preserves the voices of skilled artisans, documenting legal cases, labor relations, and domestic routines. Its records reveal early labor strikes, high literacy, and distinctive local religious traditions venerating Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nefertari.

Abandoned during political instability, the village’s isolation preserved its artifacts, giving historians a detailed view of a functioning New Kingdom community. The story of these "Servants in the Place of Truth" illuminates not only the construction of Egypt’s royal tombs but also the complex social, legal, and religious life of ordinary Egyptians who created extraordinary works.

The village was deliberately built in a secluded area near the Valley of the Kings to protect the secrecy of royal tomb locations and designs from outsiders and potential tomb robbers.

Deir el-Medina contained around 68 houses arranged along narrow streets, with homes featuring living areas, storage rooms, kitchens, and rooftop access. The village was enclosed by protective walls.

This title referred to the skilled craftsmen and artisans of Deir el-Medina, responsible for constructing and decorating the royal tombs, reflecting their prestigious and sacred role.

Yes, many inhabitants—including women—were literate, learning to read and write through family instruction. This high literacy enabled detailed record-keeping on ostraca and papyri.

The village is famous for recording the first known labor strike in history during Ramesses III’s reign, when workers protested delayed or insufficient grain rations and demanded fair treatment.