Library of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria stands as the most famous library of Classical antiquity, housing an estimated 40,000 to 400,000 scrolls at its peak—equivalent to roughly 100,000 books. This ambitious institution was conceived as a universal library, with Demetrius of Phaleron having "a large budget in order to collect, if possible, all the books in the world".

Furthermore, this remarkable center of learning was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, dedicated to the Muses. The Great Library of Alexandria contributed significantly to Alexandria becoming regarded as the capital of knowledge and learning. Notable scholars worked at the Alexandria Egypt library during the third and second centuries BC, including Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who calculated Earth's circumference with astounding accuracy. The collection grew rapidly through aggressive and well-funded policies for procuring texts, with one of the major acquisitions being the "books of Aristotle".

Historical Context of Alexandria Egypt Library

Founded in 331 BC by Alexander the Great, Alexandria rapidly evolved into a beacon of Hellenistic civilization. This coastal city became a pivotal center of learning and culture that would shape the intellectual landscape of the Mediterranean world for centuries.

Alexandria as a center of Hellenistic culture

Alexandria emerged as the intellectual capital of the ancient world, eventually eclipsing even Athens by the third century BC. The city's grandeur attracted scholars, philosophers, and scientists from across the known world, establishing it as the foremost hub of Hellenistic culture. Through royal patronage of the Ptolemies in an environment largely detached from its Egyptian surroundings, Greek culture was preserved and developed. The Mouseion and its associated Library created an unparalleled atmosphere for intellectual pursuits, allowing Alexandria to become a global knowledge capital of enormous influence.

The political landscape of Ptolemaic Egypt

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, his empire fractured among his generals, with Ptolemy I Soter claiming Egypt. The Ptolemaic dynasty would rule for nearly three centuries as the longest and final dynasty of ancient Egypt. The Ptolemies fostered Hellenistic learning while adopting Egyptian customs to legitimize their rule. Their court cultivated extravagant luxury, with the palace complex eventually occupying as much as a third of the city. Although Greeks dominated the ruling class, the Ptolemies maintained careful distinction among the population's three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and Egyptian.

Competing libraries in the ancient world

The struggle for royal supremacy among Hellenistic kingdoms extended into scholarship, sparking competition in establishing prestigious libraries. Most notable was the rivalry between Alexandria and Pergamum, whose library was built a century after Alexandria's. When King Eumenes II expanded Pergamum's library to challenge Alexandria's dominance, the Ptolemies retaliated by cutting off papyrus supplies to Pergamum. Moreover, every major Hellenistic urban center eventually established royal libraries to enhance their prestige and attract scholars. Nevertheless, Alexandria's library remained unrivaled due to the Ptolemies' unprecedented ambitions and Egypt's abundant papyrus supply.

Alexandria's strategic importance

Alexandria's location made it a vital crossing point between Asia and Europe, controlling commerce throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The city connected to the Nile via canals, allowing Egyptian grain to reach Alexandria before being shipped across the Mediterranean. After Rome conquered Alexandria in 30 BC, this strategic position gained even greater importance, as Rome depended heavily on grain imports from Egyptian granaries. The city's harbors generated constant tax revenue from trade, while emperors closely monitored Alexandria to prevent famine or rebellion.

The multicultural environment of Alexandria

Alexandria hosted a remarkably diverse population, with Greeks, Egyptians, Jews, and others coexisting in a cosmopolitan setting. The Jewish community occupied two of the city's five quarters, making it the largest Jewish community in the ancient world. The Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was produced in Alexandria. Greeks and Egyptians created a unique cultural synthesis, with graves showing mixtures of Greek and Egyptian worship. Alexandrian women followed Greek fashion yet also assimilated Egyptian customs, enjoying slightly more opportunities than their counterparts in Greece.

The Library of Alexandria aimed to collect and preserve all known knowledge from around the world. It served as a center for scholarship, research, and intellectual pursuits, housing an extensive collection of scrolls and attracting brilliant minds from various disciplines.

Architecture and Physical Structure

Situated within the Brucheion (Royal Quarter) of Alexandria, the physical structure of the Great Library formed part of the larger Mouseion complex, creating what many consider the prototype for modern university campuses.

Layout of the library complex

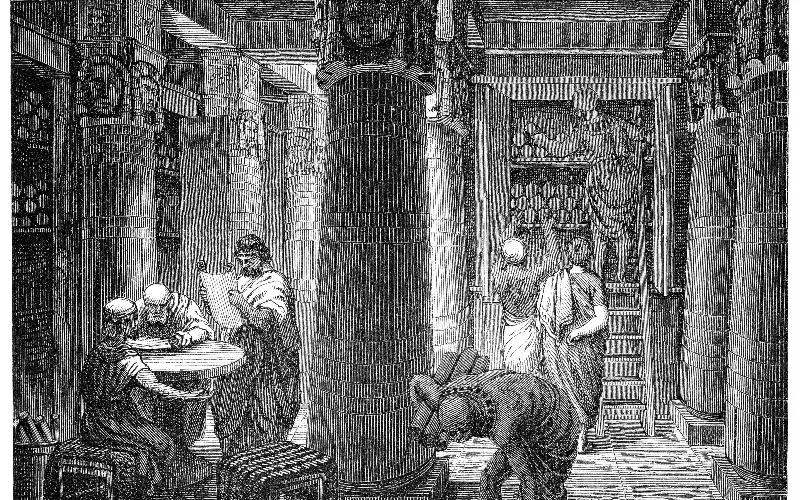

Ancient sources describe the Library of Alexandria as comprising Greek columns, a peripatos walk (colonnaded walkway), gardens, and multiple functional spaces. Despite the absence of definitive archeological evidence revealing its exact layout, historians recognize it was integrated into the Mouseion, a temple dedicated to the Muses and center of scholarly activity. This arrangement provided a comprehensive intellectual environment that supported both study and collaboration among scholars.

Connection to the royal palace

The Library existed as an integral component of the royal Ptolemaic complex. According to Strabo's account, there was a metonymic contiguity between the Museum and the royal precinct, establishing a physical connection between knowledge and political power. Additionally, the royal complex contained the Sema, where Alexander's body and Ptolemaic kings were entombed, creating a symbolic link between the preservation of knowledge and the preservation of royal legacy.

Reading rooms and lecture halls

Scholars benefited from specialized spaces including reading rooms, lecture halls, and meeting rooms. A distinctive feature was the large circular dining hall with a high domed ceiling where resident scholars ate communally. These learned individuals received salaries, free food and lodging, and exemption from taxes. Above the library's shelves, an inscription reportedly read: "The place of the cure of the soul".

Storage solutions for thousands of scrolls

The library's collection, organized by subjects with a president-priest overseeing each faculty, required innovative storage solutions. Scrolls were kept on shelves positioned half a meter from walls to maintain airflow, thereby preventing damaging mold and mildew on papyrus. This careful arrangement helped preserve the library's massive collection, estimated at between 500,000 and 700,000 works.

Archeological evidence and reconstructions

Consequently, definitive physical evidence of the original library remains elusive. Seismic activity has submerged much of ancient Alexandria underwater, and the modern city impedes archeological access. The Serapeum's remains represent the only concrete physical link to the Great Library that still exists. Even if archeologists uncovered library structures, they might be indistinguishable from other large buildings of the period.

Comparison with other ancient libraries

Unlike competing institutions, such as Pergamon's library, the Alexandria Egypt Library benefited from the Ptolemies' unprecedented commitment to collecting all knowledge. When the original collection outgrew its space, a daughter library was established in the nearby Serapeum during Ptolemy III Euergetes' reign.

Estimates vary, but the Library of Alexandria is believed to have housed between 40,000 to 400,000 scrolls at its peak, which is roughly equivalent to 100,000 books in modern terms.

The library was associated with several significant achievements, including Eratosthenes' accurate calculation of Earth's circumference, the development of critical textual methods, and the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek (the Septuagint).

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

Plan Your TripThe Burning of Library of Alexandria: Separating Myth from History

The destruction of the Library of Alexandria remains one of history's most enduring mysteries, with numerous competing narratives that have evolved over centuries.

Contemporary accounts of destruction

Initially, in 48 BCE, Julius Caesar became entangled in Egypt's civil war between Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII. Plutarch explicitly states that "Caesar was forced to repel the danger by using fire, which spread from the dockyards and destroyed the Great Library". Cassius Dio similarly mentions that "books, said to be great in number and of the finest, were burned". Yet careful analysis reveals Caesar's fire likely damaged only part of the collection, as scholarly activity continued afterward.

Later historical embellishments

Following centuries of silence, new narratives emerged. Notably, a 13th-century account claimed that in 642 CE, Caliph Omar ordered the library's scrolls burned to heat Alexandria's bathhouses for six months. However, this story appeared six centuries after the alleged event, with no contemporary chroniclers mentioning such destruction.

Archeological evidence of fires

Physical evidence remains scarce. Much of ancient Alexandria lies underwater or beneath the modern city, complicating archeological investigation.

Political motivations behind destruction narratives

Indeed, these narratives often served ideological agendas. Edward Gibbon's anti-Christian polemic in the 18th century heavily influenced later accounts. Similarly, medieval Christian writers promoted anti-Islamic narratives about the library's fate.

Modern scholarly consensus

Ultimately, contemporary historians reject the notion of a single catastrophic event destroying the library. Instead, they conclude it gradually disappeared through "centuries of decline and neglect—a loss driven by political and financial concerns and punctuated with smaller fires". By the 21st century, scholarly consensus holds that both the main library and daughter library had vanished long before the Arab conquest.

Contrary to popular belief, the Library of Alexandria wasn't destroyed in a single catastrophic event. Instead, it declined gradually over centuries due to neglect, political changes, and smaller incidents. The idea of a dramatic, one-time destruction is largely a myth.

The Library of Alexandria was a monumental center of learning in the ancient world, housing hundreds of thousands of scrolls and attracting brilliant scholars, making Alexandria the intellectual hub of its time. Its decline was gradual, shaped by neglect and political changes rather than a single catastrophic event, contrary to popular myths. Integrated with the Mouseion, it functioned much like a modern university, providing scholars with resources and privileges that fostered groundbreaking achievements, including Eratosthenes’ calculation of Earth’s circumference and the translation of the Septuagint. Though the library itself no longer exists, its legacy endures, symbolizing humanity’s enduring pursuit of knowledge and inspiring modern efforts to preserve and share intellectual heritage.

The Library of Alexandria transformed the city into the intellectual capital of the ancient world. It provided a unique environment for scholars to pursue their studies, fostered groundbreaking discoveries across various fields, and established methods for textual analysis that continue to influence modern scholarship.

The Library was founded under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 BCE) and largely organized by Demetrius of Phaleron, who oversaw the collection of scrolls from across the ancient world.

The Mouseion was a larger research and cultural institute dedicated to the Muses, functioning as a kind of ancient university. The Library of Alexandria was part of the Mouseion, providing scholars with resources, accommodations, and a space for study.

The Library aggressively collected texts by purchasing or copying works from ships docking in Alexandria. Some accounts suggest that books from private collections were temporarily borrowed, copied, and returned, contributing to the library’s rapid growth.

Notable scholars included Eratosthenes, who calculated Earth’s circumference; Euclid, a mathematician; and Callimachus, who created one of the first known bibliographies. Many others contributed to astronomy, medicine, and philosophy.

The Library’s ambition to gather all human knowledge inspired modern libraries and institutions worldwide. Its legacy represents the pursuit of universal knowledge, critical thinking, and scholarship, which continues to influence education and research today.